Unmasking The True Size Of Countries: What Maps Don't Tell You

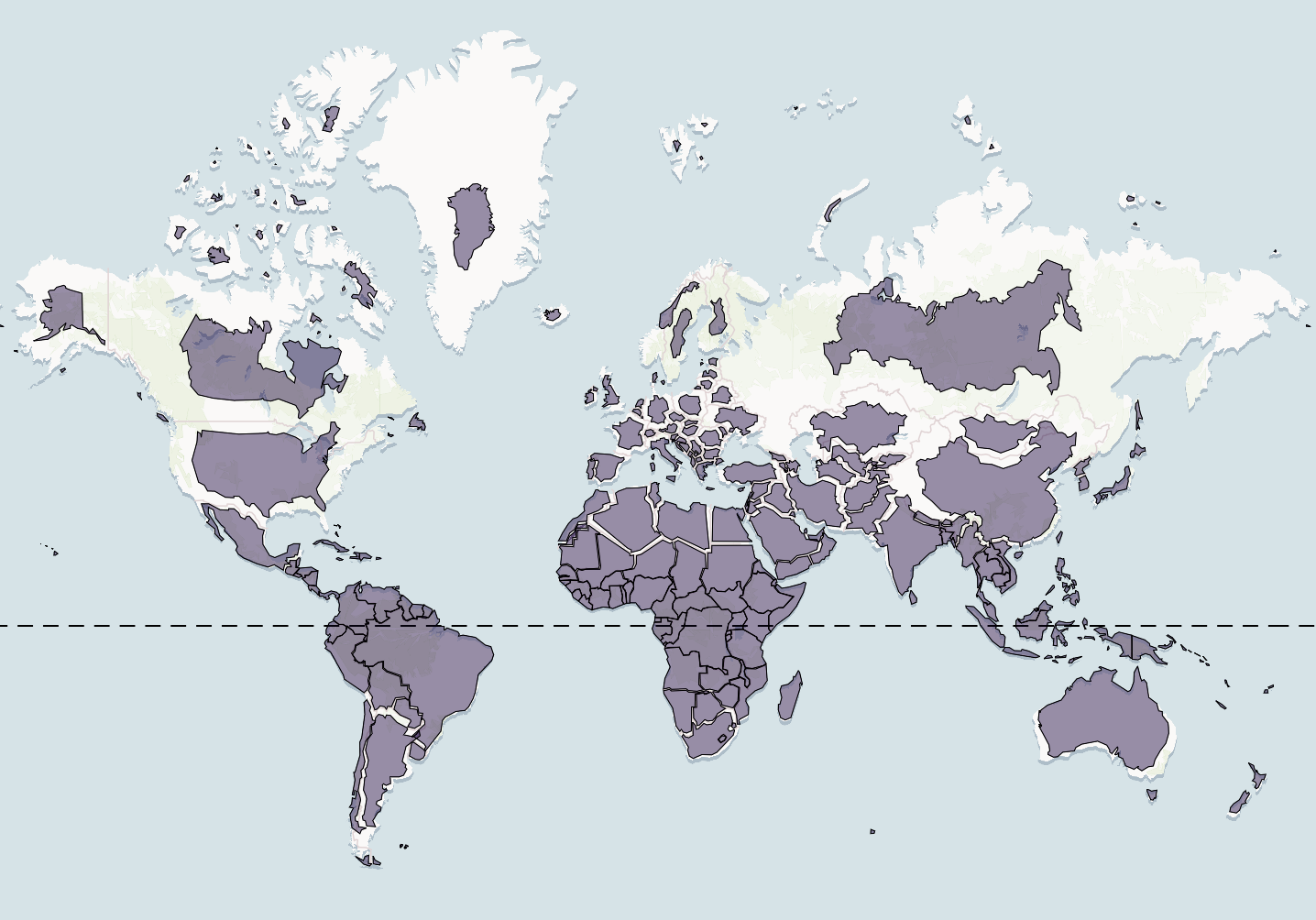

Have you ever looked at a world map and wondered if Greenland is truly as vast as Africa, or if Russia genuinely dwarfs every other nation by such a monumental margin? For most of us, the maps we grew up with, particularly those based on the Mercator projection, have shaped our understanding of global geography. However, these traditional representations, while useful for navigation, dramatically distort the relative sizes of landmasses, especially as one moves away from the equator. This pervasive distortion has led to widespread misconceptions about the true size of countries, influencing our perception of global power dynamics, resource distribution, and even our understanding of cultural diversity.

The good news is that thanks to innovative online tools and a renewed focus on accurate geographical representation, we can now challenge these ingrained perceptions. Imagine being able to drag and drop countries around an interactive map to compare their real sizes, or to see how a nation's apparent size changes as you move it closer to or further from the equator. You may be surprised at what you find, as these tools reveal the actual scale of nations, offering a more accurate picture of global geography and fostering a deeper appreciation for the world's true diversity. Understanding the true size of countries helps us better comprehend our world's real geography, moving beyond the visual biases of conventional maps.

Table of Contents

- The Deceptive Beauty of Traditional Maps

- The Birth of a New Perspective: True Size Tools

- Unveiling Surprising Comparisons: Greenland vs. Africa & More

- Beyond Mercator: Alternative Map Projections

- Why Does True Size Matter? Perception and Understanding

- Practical Applications: Education and Global Awareness

- The Science Behind the Distortion: Latitude's Role

- Empowering Your Geographic Understanding

The Deceptive Beauty of Traditional Maps

For centuries, the Mercator projection has been the standard for world maps. Developed in 1569 by Gerardus Mercator, this cylindrical map projection was revolutionary for its time, providing a reliable way for sailors to navigate. Its key advantage lies in its ability to represent lines of constant true bearing (rhumb lines) as straight segments, making it incredibly useful for maritime travel. However, this navigational convenience comes at a significant cost: extreme distortion of area, especially as one moves away from the equator towards the poles. This distortion means that countries closer to the poles appear much larger than they are in reality, while those near the equator are represented more accurately but often appear smaller than their actual landmass relative to their northern counterparts.

This common type of map hugely distorts its true size, leading to a skewed understanding of global geography. For instance, countries like Canada, Russia, and Greenland appear disproportionately vast on a Mercator map. This visual bias has been so pervasive that it's deeply ingrained in our collective consciousness. Most of us grew up looking at distorted world maps that misrepresent the true size of countries, never questioning the accuracy of what we saw. The visual impact of these maps is profound, subtly shaping our perception of global power, resource distribution, and even geopolitical significance based on perceived landmass, rather than actual area. It's a classic example of how a tool designed for one specific purpose (navigation) inadvertently created widespread misconceptions when applied broadly (general world representation).

Understanding the Mercator Projection's Flaws

The core issue with the Mercator projection stems from its method of projecting a spherical Earth onto a flat, two-dimensional surface. Imagine peeling an orange and trying to flatten its peel without tearing or stretching it – it's impossible without some form of distortion. The Mercator projection addresses this by stretching areas at higher latitudes to maintain angles and shapes, which is crucial for navigation. This stretching, however, dramatically inflates the perceived size of landmasses further from the equator. For example, Greenland, which is relatively close to the North Pole, appears enormous, often comparable in size to Africa on a Mercator map. Yet, in reality, Africa is approximately 14 times larger than Greenland. Similarly, Alaska often looks bigger than Mexico, even though Mexico is significantly larger.

This distortion affects not only the perception of area but also the shape of countries, though shape distortion is less pronounced near the equator. The further north or south you go, the more exaggerated the stretching becomes, making regions like Antarctica appear as a colossal, impossibly wide landmass spanning the entire bottom of the map. The map we see, particularly the Mercator, is not telling the full truth about the real size of countries. It's a compromise that prioritizes angular accuracy over area accuracy, a trade-off that has profound implications for our understanding of global scale. Understanding how the Mercator projection distorts the sizes of countries, especially near the poles, is the first step in correcting these long-held misconceptions.

- The 48 Laws Of Power

- Lieutenant Dan Tampa

- Haventunin Leaks

- Imagenes De Buenos Dias

- Gotta Be Quicker Than That

The Birth of a New Perspective: True Size Tools

In recent years, the advent of interactive online tools has revolutionized how we perceive global geography. Challenging our conventional understanding, applications like "The True Size of Countries" have emerged as powerful educational resources. Created by James Talmage and Damon Maneice, the site uses Google Maps to show the actual size of different countries and landmasses. These innovative platforms allow users to dynamically explore the real scale of countries, directly addressing the distortions inherent in traditional maps. By providing a hands-on experience, these tools transform abstract geographical concepts into tangible, visual comparisons, making learning both engaging and incredibly insightful.

The true size of countries map is a powerful tool that corrects misconceptions created by distorted projections like Mercator. It's not just about correcting a map; it's about correcting a worldview shaped by inaccurate visual information. These tools offer a fresh perspective, enabling anyone to discover the true size of nations and see accurate maps that challenge misconceptions about country sizes. They represent a significant leap forward in geographic education, moving beyond static, misleading representations to dynamic, accurate ones. Tools like The True Size and alternative map projections help correct these misconceptions, offering a more accurate picture of global geography and empowering users to find out the real size of countries for themselves.

How Interactive Tools Reveal the Truth

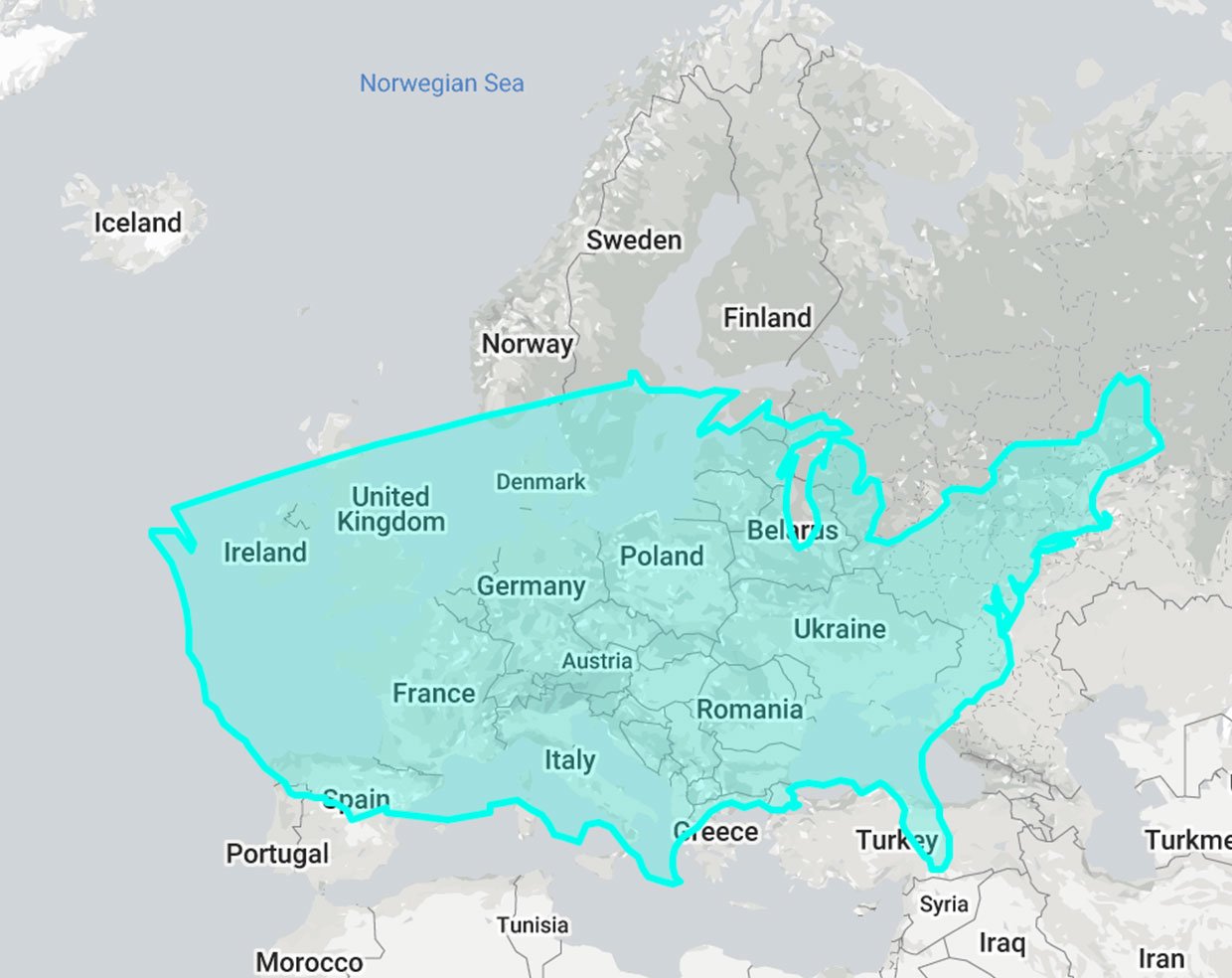

The brilliance of interactive true size comparison tools lies in their simplicity and immediate visual impact. They operate on a fundamental principle: by allowing users to drag and drop countries around the map, the tools dynamically adjust the country's size to reflect its true area relative to its position on the Mercator projection. This means that as you drag a country from, say, northern Europe down towards the equator, you'll witness it "shrink" to its actual size, often revealing just how much it was exaggerated at higher latitudes. Conversely, dragging an equatorial country north will make it appear to expand, demonstrating the Mercator effect in reverse. This interactive animation shows some countries shrinking to show their true size, providing a vivid demonstration of map distortion.

Our true size comparison tool lets you drag and compare countries to see their real sizes relative to each other. You can search the name of the country and compare the size of the country by dragging its polygon shape. This interactive map shows the real size of countries on a Mercator projection map, but with the crucial ability to move and compare. For example, you can overlay USA over Africa, China, or Europe to see how they truly compare in landmass, area, and even population (though population is a separate metric). You may be surprised at what you find. This allows for direct, real-time comparisons that static maps simply cannot offer. The ability to customize the map with color, opacity, and equator settings and share your custom map with anyone further enhances its utility, making it a great tool for educators and anyone curious about global geography.

Unveiling Surprising Comparisons: Greenland vs. Africa & More

The most striking revelations from using a true size map often come from comparing countries that appear vastly different on traditional Mercator maps. The classic example, often used to highlight the Mercator's distortion, is the comparison between Greenland and Africa. On a standard map, Greenland looks roughly the same size, if not larger, than the entire continent of Africa. However, when you use an interactive tool to compare their real sizes, you discover that Africa is, in fact, approximately 14 times larger than Greenland. Is Greenland really as big as all of Africa? The answer is a resounding no, and the interactive map powerfully demonstrates this.

Another eye-opening comparison involves Russia. On a Mercator map, Russia appears to span an almost unimaginable portion of the northern hemisphere, dwarfing nearly every other country. While Russia is indeed the largest country by land area, its perceived size on traditional maps is significantly exaggerated due to its high latitude. When you drag Russia down towards the equator on an interactive map, its true size becomes apparent, revealing that while still massive, it's not quite the gargantuan landmass we've been led to believe. Suddenly, those size differences don’t seem so great any more. Similarly, Canada, another large country at high latitudes, also appears much smaller when moved to equatorial regions. How big is the United States compared to Africa? Or how about Massachusetts compared to Estonia? Try entering the names of countries and states on this interactive map, and then dragging them around to compare them by superimposing one on top of another. These direct visual comparisons are incredibly effective in correcting long-held misconceptions and fostering a more accurate mental map of the world's true size of countries.

Beyond Mercator: Alternative Map Projections

While interactive tools allow us to correct the Mercator's distortions on the fly, cartographers have long sought alternative map projections that offer different compromises. No flat map can perfectly represent a sphere without some form of distortion – it's a fundamental mathematical impossibility. However, different projections prioritize different aspects: some preserve area, others preserve shape, distance, or direction. Understanding these alternatives is crucial for a comprehensive grasp of global geography beyond the familiar Mercator. The choice of map projection says a lot about what properties are considered most important for a given purpose. Exploring these different projections helps us appreciate the complexity and artistry involved in mapping our spherical world onto a flat surface, each with its own strengths and weaknesses.

The Eckert IV Projection: Preserving Area

One of the most notable alternatives for accurately representing land area is the Eckert IV projection. Crucially, Eckert IV preserves true areas. This means that every country’s shape is distorted, but its area on the map is proportional to its real area. Unlike the Mercator, which sacrifices area accuracy for shape and angular accuracy, the Eckert IV makes the opposite trade-off. While the shapes of continents and countries might appear stretched or compressed in certain directions, their relative sizes are maintained. This makes Eckert IV ideal for world maps where relative country size must be accurate, such as those used for statistical mapping, population density, or resource distribution studies. For educational purposes, especially when teaching about global landmasses and their actual proportions, the Eckert IV projection offers a far more truthful representation than the Mercator. It's a powerful visual reminder that perceived size isn't always actual size.

Other Noteworthy Projections: Dymaxion, Spilhaus

Beyond Eckert IV, many other fascinating map projections exist, each designed to highlight specific aspects of the Earth. The Dymaxion map of the world, for instance, developed by Buckminster Fuller, presents the Earth's landmasses as a single, continuous island in a sea, minimizing distortion of shapes and relative sizes. It's typically presented on the surface of an unfolded icosahedron, which can then be flattened. This projection offers a unique perspective, emphasizing the interconnectedness of continents and challenging traditional Eurocentric views of the world. Another intriguing example is the Spilhaus world ocean map projection with sea surface temperature. This projection places the oceans at the center, emphasizing their role in global climate and interconnectedness, rather than the landmasses. While not directly focused on the true size of countries, these alternative projections underscore the vast array of ways to represent our planet, each with its own biases and benefits, further illustrating that the size of countries can be influenced by various factors such as map projections, cultural biases, and historical context.

Why Does True Size Matter? Perception and Understanding

Understanding the true size of countries goes beyond mere geographical curiosity; it has profound implications for our perception of the world and our place within it. When we consistently view maps that exaggerate the size of certain regions, it can subtly influence our understanding of their geopolitical importance, economic power, and even cultural significance. For example, if a country appears vast on a map, we might unconsciously associate it with greater power or influence, regardless of its actual population or GDP. This can perpetuate biases and stereotypes, affecting international relations, trade negotiations, and even humanitarian aid efforts. The true size of countries map is a powerful tool that corrects these misconceptions, providing a more accurate basis for understanding global dynamics.

Moreover, accurate geographical understanding is fundamental to informed decision-making. Whether discussing climate change, resource management, or global population distribution, having a correct mental model of landmasses is crucial. If we believe a country is larger than it is, we might overestimate its capacity for agriculture or its vulnerability to environmental changes. Conversely, underestimating the size of a populous nation could lead to misjudgments about its resource needs or impact. By exploring the real size of countries, we can gain a deeper appreciation for the world’s diversity and the actual scale of its challenges and opportunities. It fosters a more nuanced and accurate understanding of our planet, moving beyond the visual biases of distorted maps.

Practical Applications: Education and Global Awareness

The interactive tools that reveal the true size of countries are not just fascinating novelties; they are invaluable educational resources. For educators, these tools are a game-changer. They provide a dynamic and engaging way to teach students about map projections, geographical distortions, and the actual scale of our planet. Instead of simply telling students that Greenland isn't as big as Africa, teachers can now show them, allowing students to experience the correction firsthand by dragging and dropping countries around the map to compare their relative size. This hands-on approach makes abstract concepts concrete and memorable, fostering a deeper, more intuitive understanding of world geography.

Beyond the classroom, these tools contribute significantly to global awareness. In an increasingly interconnected world, understanding the real scale of nations is vital for informed citizenship. It helps us contextualize news events, appreciate cultural differences, and engage with global issues more effectively. Whether it's discussing the impact of deforestation in the Amazon (which is truly vast) or the population density of a seemingly small but densely populated nation, having an accurate mental map is essential. Compare the true country sizes with interactive map tool, and you'll find yourself questioning long-held beliefs, leading to a richer and more accurate understanding of our world. It's about empowering individuals to see the world as it truly is, free from the visual biases of outdated cartography.

The Science Behind the Distortion: Latitude's Role

The distortion of landmasses on a Mercator map is a direct consequence of latitude. As one moves away from the equator (0 degrees latitude) towards the poles (90 degrees north or south latitude), the parallels of latitude on the map are spaced further and further apart. On a globe, the lines of longitude converge at the poles, but on a Mercator map, they are drawn as parallel vertical lines. To compensate for this, the map stretches the landmasses horizontally as well, maintaining their shape but vastly inflating their area. This means that a country at 60 degrees latitude will appear twice as wide as it actually is, and its area will be four times larger than its true size on the map, relative to an equivalent area at the equator.

This mathematical stretching explains why countries like Russia, Canada, and Greenland appear so disproportionately large. Discover the true size of countries as they change across different latitudes, and you'll witness this principle in action. The interactive map applications that challenge our conventional understanding of global geography by illustrating the true sizes of countries do so by accounting for this latitude-based distortion. They effectively "undo" the stretching as you move a country to a different latitude, revealing its actual dimensions. See an interactive animation and a graph of the difference between real and apparent sizes of countries to truly grasp the extent of this phenomenon. It’s a compelling demonstration of how mathematical projections can profoundly alter our visual perception of reality.

Empowering Your Geographic Understanding

In an age where information is constantly at our fingertips, the ability to discern accurate data from misleading representations is more crucial than ever. Our journey through the world of map projections and the true size of countries reveals that what we see isn't always what is. Traditional maps, particularly those based on the Mercator projection, distort the relative sizes of landmasses, especially as one moves away from the equator. But now, with powerful interactive tools, we have the means to correct these long-standing misconceptions and gain a more authentic understanding of our planet's geography.

By actively engaging with these resources – dragging and dropping countries, comparing their real sizes, and exploring alternative projections like the Eckert IV – you empower yourself with a more accurate mental map of the world. This enhanced geographic literacy not only satisfies curiosity but also provides a more informed perspective on global issues, cultural diversity, and the true scale of our shared planet. We encourage you to explore these interactive maps, challenge your own perceptions, and discover the true scale of nations. What surprising comparisons will you uncover? Share your most astonishing findings in the comments below, and let's continue to learn and grow our understanding of the world, one accurately sized country at a time.

True Size Of Countries

The True Size of Countries: The World Map Looks Different Than You

This Map Lets You Compare The Relative Size of Countries