Mastering The Art Of Sword Drawing: Techniques & History

The ancient art of sword drawing, often shrouded in mystery and depicted with dramatic flair in films, is far more than just unsheathing a blade. It is a profound discipline, a dance of precision, speed, and intent that has been honed over centuries. From the swift, decisive movements of a samurai on the battlefield to the meditative grace of modern martial arts practitioners, the act of drawing a sword is a testament to mastery over oneself and the weapon. This intricate skill, central to many traditional martial arts, demands a deep understanding of body mechanics, spatial awareness, and mental fortitude. It’s a skill that speaks volumes about the practitioner's dedication and understanding of their craft.

Delving into the world of sword drawing reveals a rich tapestry of history, philosophy, and practical application. Whether you are a martial artist seeking to deepen your understanding, a history enthusiast curious about ancient combat techniques, or simply fascinated by the elegance of the blade, comprehending the nuances of sword drawing offers a unique perspective into the warrior's path. This article will guide you through the core principles, historical context, and practical aspects of this captivating art form, providing insights that go beyond mere theatrical portrayal.

Table of Contents

- The Allure of the Draw: Why Sword Drawing Captivates

- Historical Roots of Sword Drawing: From Battlefield to Dojo

- Fundamental Principles of Effective Sword Drawing

- The Anatomy of a Perfect Draw: Key Stages

- Training Methodologies for Sword Drawing Mastery

- Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them in Sword Drawing

- Beyond Technique: The Mental Game of Sword Drawing

- Choosing Your Blade: Swords for Sword Drawing Practice

The Allure of the Draw: Why Sword Drawing Captivates

There's an undeniable mystique surrounding the act of sword drawing. It's often portrayed as the ultimate expression of readiness, a sudden burst of power from a state of calm. This captivating quality stems from several factors. Firstly, the visual spectacle is profound: a flash of steel emerging from its scabbard, often accompanied by the subtle hiss of metal against wood or leather, immediately commands attention. This dramatic unveiling transforms a seemingly passive object into a dynamic instrument of action. Secondly, the underlying skill required is immense. A truly masterful sword drawing is not just about speed, but about seamless fluidity, control, and economy of motion. It represents years of dedicated practice, an almost intuitive understanding of the weapon and one's own body. The efficiency with which a skilled practitioner can transition from a relaxed stance to a combat-ready posture, with the blade poised for action, is a testament to the discipline involved. This combination of visual appeal and profound underlying skill makes sword drawing a perpetual source of fascination for both practitioners and observers alike. It embodies the essence of martial arts: readiness, precision, and the controlled application of power.

Historical Roots of Sword Drawing: From Battlefield to Dojo

The practice of sword drawing, particularly as a formalized martial art, has deep roots in various cultures, most notably in feudal Japan with the development of Iaijutsu and later Iaido. While warriors across the globe historically drew their swords, the Japanese tradition elevated it to an art form, emphasizing not just the practical combat application but also mental discipline and spiritual development. In ancient Japan, the ability to draw a sword quickly and effectively was a matter of life and death, especially for samurai who might face sudden ambushes or duels. The katana, with its curved blade and single cutting edge, was ideally suited for a drawing cut, where the act of unsheathing itself could be the first strike. Early forms of Iaijutsu focused on practical, battlefield-oriented techniques, often performed from a seated position to counter unexpected attacks while resting or negotiating. These techniques were designed to provide a decisive advantage in close quarters, allowing the warrior to engage an opponent before they could fully react.

Over centuries, as warfare evolved and the samurai class transitioned from battlefield combatants to administrators and philosophers, the emphasis shifted. Iaijutsu gradually evolved into Iaido, retaining its combat effectiveness but placing greater importance on the spiritual and meditative aspects of practice. The precise movements, breath control, and mental focus became tools for self-improvement and character development. Schools (ryu) developed their own unique forms (kata) of sword drawing, each with specific nuances and philosophies. From the dynamic, powerful draws of Muso Jikiden Eishin-ryu to the more subtle, flowing movements of other traditions, each school offered a distinct path to mastery. Today, Iaido continues to be practiced worldwide, preserving these historical techniques while offering a profound path to personal growth and a deeper connection to the rich legacy of the sword. The historical evolution of sword drawing from a brutal necessity to a refined art form highlights its enduring appeal and the depth of its principles.

Fundamental Principles of Effective Sword Drawing

Effective sword drawing is built upon a foundation of fundamental principles that transcend specific styles or techniques. These principles ensure efficiency, power, and safety. Firstly, the concept of "economy of motion" is paramount. Every movement should be purposeful, without wasted effort or unnecessary flourishes. The path of the blade from scabbard to target should be the most direct and efficient possible, minimizing the time an opponent has to react. Secondly, "body unity" is crucial. The draw should not be just an arm movement; it should involve the entire body, from the feet grounding you to the core providing rotational power. This ensures that the force generated comes from the whole body, not just isolated muscles, leading to a more powerful and stable draw. Thirdly, "awareness of the saya" (scabbard) is vital. The saya is not merely a sheath; it is an integral part of the drawing process. The non-dominant hand, which holds the saya, guides the blade and provides leverage, ensuring a smooth and controlled release. The saya hand often acts as a counterweight and a pivot point, allowing the blade to emerge cleanly without snagging or making excessive noise. A common mistake is to ignore the saya, leading to clumsy or incomplete draws. Mastering the interplay between the sword hand and the saya hand is a hallmark of skilled sword drawing. Finally, "intent" is an often-overlooked principle. The draw should be executed with clear purpose and focus, not just mechanical repetition. This mental engagement imbues the technique with vitality and effectiveness, preparing the practitioner for immediate action. These principles form the bedrock upon which all advanced sword drawing techniques are built, emphasizing that mastery is not just about speed, but about intelligent and integrated movement.

- Snaptroid 20

- Natasha Klauss

- Saiveon Hopkins

- %D9%8A%D8%A7%D8%B3%D9%85%D9%8A%D9%86 %D8%B2%D8%A8%D8%A7%D8%B1%D9%8A

- What Does Wyll Mean

Stance and Grip: The Foundation

Before any movement of the blade, a solid foundation is essential, and this begins with stance and grip. A proper stance provides stability, balance, and the ability to generate power through ground reaction forces. In most sword drawing styles, the stance involves a balanced distribution of weight, often with one foot slightly forward, allowing for quick shifts in direction or bursts of movement. The hips are typically relaxed and aligned, ready to rotate and drive the draw. The posture should be upright but not rigid, allowing for natural movement and breath. A common stance in Iaido, for example, might be a relaxed hachiji-dachi (natural stance) or a more formal seiza (kneeling position), each requiring specific body alignment to facilitate the draw. The grip on the sword is equally critical. It should be firm yet relaxed, allowing for subtle adjustments and preventing tension that can impede fluid motion. The hands typically grip the tsuka (handle) with the pinky and ring fingers providing the primary securement, while the thumb and index finger allow for more nuanced control. The grip should be centered, ensuring that the blade's balance point is naturally felt. Over-gripping or "death-gripping" the sword is a common error that leads to stiff movements, reduced power, and quick fatigue. A proper grip allows the sword to become an extension of the body, facilitating a smooth and powerful sword drawing action. This foundational understanding of stance and grip is the first step towards mastering the intricate art of drawing the sword.

The Anatomy of a Perfect Draw: Key Stages

A perfect sword drawing is not a single, instantaneous action but a series of interconnected, fluid stages, each crucial for the overall success of the technique. Understanding these stages allows for systematic practice and refinement. The process typically begins with the practitioner in a state of readiness, often with the sword sheathed at the hip. The first stage, known as "saya-biki" or "saya-banare," involves the initial movement of the scabbard away from the body, creating a small gap for the blade to emerge. This is not a draw of the sword itself, but a preparation. Simultaneously, the sword hand begins to adjust its grip, preparing for the powerful pull. The second stage is the actual "nuki-tsuke," the initial cutting draw where the blade begins to exit the saya and makes its first contact with the target. This is often a horizontal or upward diagonal cut, designed to create immediate impact. Following nuki-tsuke, the blade continues its arc, fully clearing the saya in a movement often referred to as "kirioroshi" or "furi-kaburi," which positions the sword for a powerful downward or finishing cut. The body's rotation and forward momentum are critical here, channeling power into the blade. The final stages involve "chiburi," the symbolic flicking of blood from the blade, and "noto," the controlled and safe re-sheathing of the sword. Each of these stages requires precise timing, coordinated body movement, and mental focus. The seamless transition from one stage to the next, without hesitation or wasted motion, defines a truly masterful sword drawing. It is this intricate choreography of movements that makes the art so challenging and rewarding to learn.

Nuki-tsuke: The Initial Cut

Among the various stages of sword drawing, "nuki-tsuke" stands out as arguably the most critical. This is the moment the blade first engages the target as it leaves the scabbard. It is not merely the act of pulling the sword out; it is the first strike, a cutting action performed simultaneously with the draw. The effectiveness of nuki-tsuke lies in its surprise and speed. Because the sword is still partially sheathed, the movement is compact and difficult for an opponent to anticipate. The cut is typically performed with the monouchi (the cutting portion of the blade, roughly the first third from the tip), utilizing the forward momentum of the draw and the rotational power of the hips. The saya hand plays a vital role in nuki-tsuke, pushing the scabbard backward and slightly away from the body, providing the necessary counter-leverage for the blade to slide out smoothly and efficiently. This coordinated action allows for a powerful, shearing cut. A common mistake is to simply "pull" the sword out without integrating the cutting motion, which results in a slower, less effective draw. Mastering nuki-tsuke requires thousands of repetitions, focusing on the precise angle of the blade, the coordination of both hands, and the full engagement of the body. It embodies the principle that the draw is not just about unsheathing, but about immediate, decisive action. This initial cut sets the tone for the entire engagement, often determining the outcome in a real-world scenario, making it a cornerstone of effective sword drawing.

Training Methodologies for Sword Drawing Mastery

Achieving mastery in sword drawing is a journey that requires consistent, disciplined training. The methodologies employed are often rooted in centuries-old traditions, emphasizing repetition, precision, and mindful practice. One of the primary methods is "kata" or pre-arranged forms. These sequences of movements simulate various combat scenarios, allowing practitioners to internalize the correct techniques for drawing, cutting, and re-sheathing the sword without the dangers of live sparring. Kata training focuses on perfecting every detail: the angle of the blade, the timing of the draw, the coordination of the body, and the intent behind each movement. Repetition of kata builds muscle memory, transforming conscious effort into fluid, instinctive action. Another crucial aspect is "suburi," or solo cutting drills. These involve repeated swings and cuts with the sword, often without a specific target, to develop strength, proper form, and a deep understanding of the blade's trajectory and balance. Suburi helps in refining the "tenouchi" (the grip and wrist action) and developing powerful, controlled cuts that originate from the core, not just the arms. Beyond physical drills, mental training is equally important. This includes "zanshin," a state of continued awareness and readiness even after a technique is completed, and "mushin," a state of no-mind or empty mind, where actions flow spontaneously without conscious thought. Visualization exercises, where practitioners mentally rehearse the sword drawing techniques, also play a significant role in refining movements and building confidence. Furthermore, training often involves the use of specialized equipment such as "iaito" (unsharpened practice swords) for safety, and later "shinken" (live blades) under expert supervision for advanced practitioners. The emphasis across all methodologies is on quality over quantity, ensuring that each repetition reinforces correct form and principles. This holistic approach to training ensures that practitioners develop not only physical prowess but also mental discipline and a profound respect for the art of sword drawing.

Solo Practice and Kata

For aspiring practitioners of sword drawing, solo practice and the diligent study of kata form the backbone of their training. Unlike partner drills or sparring, solo practice allows for focused, uninterrupted refinement of technique. It is in these solitary moments that a practitioner can meticulously analyze every micro-movement, identify flaws, and work towards seamless execution. Kata, or pre-arranged forms, are sequences of sword drawing techniques designed to teach specific principles and scenarios. Each kata tells a story, simulating an attack from a particular direction or a response to a specific threat. By repeatedly performing these forms, practitioners internalize the precise body mechanics, timing, and intent required for effective sword drawing. The repetition builds muscle memory, allowing the movements to become second nature. Moreover, solo kata practice is not just physical; it is a meditative discipline. The focus required to execute each movement with precision, to control breath, and to maintain awareness cultivates mental fortitude and presence. It's an opportunity to connect deeply with the weapon and one's own body, refining not just the technique but also the spirit. While solo practice is foundational, it's crucial to seek guidance from experienced instructors. An instructor can provide critical feedback, correct subtle errors that might go unnoticed in solo training, and offer insights that accelerate learning. However, the bulk of the hard work, the thousands of repetitions required to truly engrain the movements, must come from dedicated solo practice. This commitment to individual refinement through kata is what transforms a novice into a master of sword drawing, making the blade an extension of their will.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them in Sword Drawing

Despite its apparent simplicity, sword drawing is fraught with common pitfalls that can hinder progress and even lead to injury. Recognizing and actively avoiding these errors is crucial for effective learning. One of the most frequent mistakes is "tension." Practitioners often grip the sword too tightly or stiffen their shoulders and arms, which restricts fluid movement and reduces power. A tense draw is slow, inefficient, and telegraphs intent. To avoid this, focus on a relaxed grip (firm but not crushing) and maintain a loose, mobile upper body. Another pitfall is "disconnecting the saya hand." The non-dominant hand, which holds the scabbard, is often neglected, leading to the sword snagging or an awkward, noisy draw. The saya hand should actively guide the blade and provide counter-leverage. Practice coordinating both hands, ensuring the saya moves in harmony with the sword. "Lack of hip rotation" is another common error. Many beginners rely solely on arm strength to draw, neglecting the powerful rotational force that can be generated from the hips and core. The draw should be initiated from the lower body, with the hips leading the movement, transferring power efficiently to the blade. Furthermore, "improper blade angle" can lead to the blade scraping the inside of the saya, dulling the edge, or causing unnecessary friction. The blade should exit the saya at a precise angle, often along the mune (spine) of the blade, minimizing contact with the saya's interior. This requires careful attention to the wrist and forearm positioning during the draw. Finally, "ignoring noto" (re-sheathing) is a significant oversight. A safe and controlled noto is as important as the draw itself, demonstrating complete mastery and respect for the blade. Rushing noto can lead to injury or damage to the sword. By being mindful of these common pitfalls and consciously working to correct them, practitioners can significantly improve their sword drawing technique, making it more efficient, powerful, and safe. It's a continuous process of self-correction and refinement.

Rushing the Draw: Speed vs. Precision

One of the most tempting, yet detrimental, pitfalls in sword drawing is the impulse to prioritize speed over precision. Beginners often equate a fast draw with an effective draw, leading them to rush through the movements without proper control or technique. While speed is undoubtedly a component of effective sword drawing, it is a byproduct of precision, not its primary goal. Rushing the draw typically results in sloppy movements, a loss of balance, and a significant reduction in power and accuracy. When a practitioner rushes, they often skip crucial stages, such as proper saya-biki or full hip rotation, relying instead on brute arm strength. This not only makes the draw less effective but also increases the risk of injury, either to themselves or damage to the sword and scabbard. For instance, a rushed draw might cause the blade to scrape violently against the saya, dulling the edge or even chipping the saya's mouth. Instead of focusing on raw speed, the emphasis should be on executing each stage of the sword drawing with meticulous precision, ensuring fluid transitions and full body engagement. Once the movements are perfectly precise and effortless, speed will naturally follow. It's akin to a musician practicing scales slowly and accurately before attempting a fast piece; the speed comes from ingrained accuracy. A truly fast draw is one that appears effortless because every movement is perfectly timed and efficient, not because it's hurried. Experienced instructors often advise students to "draw slowly, then slowly faster," emphasizing that control and form must always precede velocity. This patient approach to training ultimately leads to a draw that is not only fast but also powerful, accurate, and safe, embodying the true essence of sword drawing mastery.

Beyond Technique: The Mental Game of Sword Drawing

While physical technique forms the visible foundation of sword drawing, the true mastery lies in the mental game. The ability to draw a sword effectively is as much about the mind as it is about the body. Concepts like "zanshin" (remaining mind/awareness) and "mushin" (empty mind) are central to advanced practice. Zanshin refers to the state of continued vigilance and awareness, even after a technique is completed. It means being prepared for any follow-up action or unforeseen circumstances. In sword drawing, zanshin ensures that the practitioner is not just focused on the draw itself, but on the potential consequences and the environment around them. This heightened state of awareness allows for immediate adaptation and response, transforming a mere physical action into a strategic maneuver. Mushin, on the other hand, is a state of mind where actions flow spontaneously without conscious thought or hesitation. It is the culmination of countless repetitions and deep understanding, where the technique becomes an instinctive extension of the practitioner's will. In a state of mushin, there is no fear, no doubt, and no internal monologue to impede the action. The draw simply happens, perfectly timed and executed. Achieving mushin requires extensive meditation, visualization, and a willingness to let go of conscious control. Furthermore, mental fortitude plays a crucial role in dealing with pressure. Whether in a competitive setting or a simulated combat scenario, the ability to remain calm, focused, and decisive under duress is paramount. This mental resilience is cultivated through consistent practice, self-reflection, and the disciplined pursuit of perfection. The mental game elevates sword drawing from a mere physical skill to a profound discipline that sharpens not only the body but also the mind and spirit, making it a holistic path to self-mastery. The true power of a sword drawing is often found in the stillness and clarity of the mind before the blade even moves.

Choosing Your Blade: Swords for Sword Drawing Practice

The choice of sword for sword drawing practice is a critical decision that impacts safety, learning, and progression. For beginners, safety is paramount, and therefore, live blades (shinken) are generally not recommended. The most common and safest option for initial sword drawing practice is the "iaito." An iaito is an unsharpened, blunted practice sword, typically made of an aluminum alloy or stainless steel. While it has the weight and balance similar to a live katana, its dull edge eliminates the risk of accidental cuts, making it ideal for learning the intricate movements of sword drawing. The saya (scabbard) of an iaito is also designed for practice, allowing for smooth draws and re-sheathing. For more advanced practitioners, or those transitioning to cutting practice (tameshigiri), a "shinken" (live, sharpened blade) may be used under strict supervision. Shinken are typically made of high-carbon steel and are extremely sharp, requiring immense respect and caution. Their use is reserved for those who have demonstrated a high level of proficiency and control with an iaito. Another option, particularly for historical European martial arts (HEMA) or general Western sword drawing, might be a "blunt" or "feder" for sparring, which are designed to absorb impact, or a "sharpened replica" for solo forms, though these also require extreme caution. The key considerations when choosing a blade for sword drawing are: its weight and balance (should feel comfortable and natural in your hands), the quality of its construction (especially the saya and tsuka for durability and safety), and its suitability for your current skill level. Always consult with your instructor before purchasing a sword, as they can provide tailored advice based on your specific training needs and the style of sword drawing you are pursuing. Investing in a quality practice sword is an investment in your safety and your journey towards mastering the art of sword drawing.

Conclusion

The art of sword drawing is a captivating discipline that transcends mere physical action, embodying centuries of martial tradition, mental fortitude, and profound self-mastery. From the meticulous precision of its fundamental principles to the nuanced mental game required for true proficiency, sword drawing offers a rich path for personal development. It teaches not just how to wield a blade, but how to cultivate awareness, control, and decisive action in every aspect of life. The journey from a hesitant beginner to a fluid, confident practitioner is one of dedication, constant refinement, and a deep respect for the blade and its history. By understanding its historical roots, mastering its core techniques, and avoiding common pitfalls, anyone can embark on this rewarding path.

We hope this comprehensive guide has illuminated the intricate beauty and profound depth of sword drawing. What aspects of sword drawing fascinate you the most? Have you ever considered practicing a martial art that involves the blade? Share your thoughts and experiences in the comments below! If you found this article insightful, please consider sharing it with others who might appreciate the elegance and discipline of this ancient art. Explore our other articles for more deep dives into martial arts and historical combat.

Sword Drawing - How To Draw A Sword Step By Step

How to Draw a Sword | Easy Drawing Guides

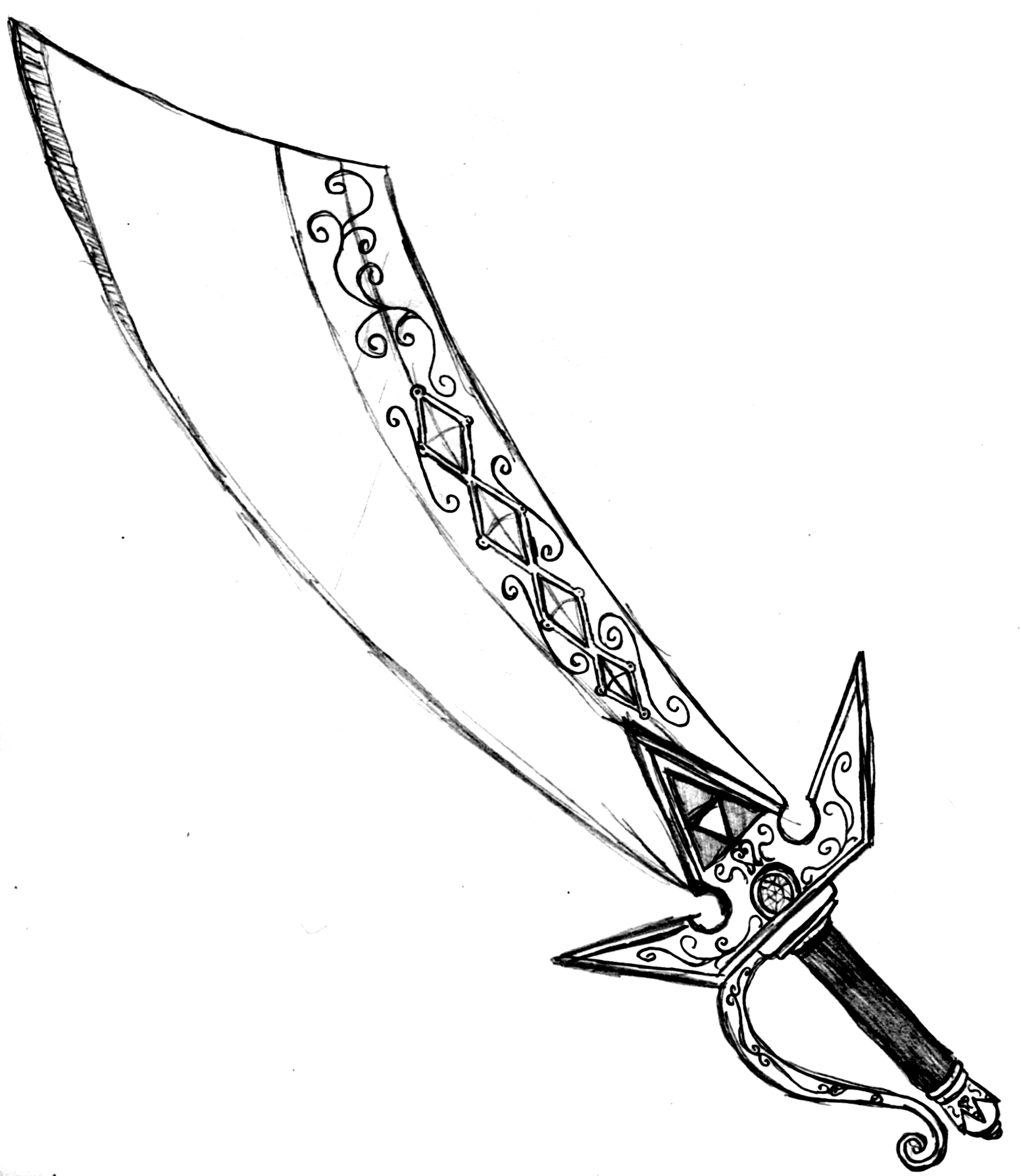

Swords Drawing at GetDrawings | Free download